One hopes Rep. Jesse Kremer, a Wisconsin Assemblyman, is that state’s lone lawmaker so detached from science, fossil records, human history and reality itself to believe the Earth is 6,000 years old.

To believe such malarkey, Wisconsin lawmakers must also believe the state’s plucky native tribes once battled triceratops, pterodactyls and Tyrannosaurus Rex’s contemporaries with atlatls and stone axes.

Surely they’re not that kooky.

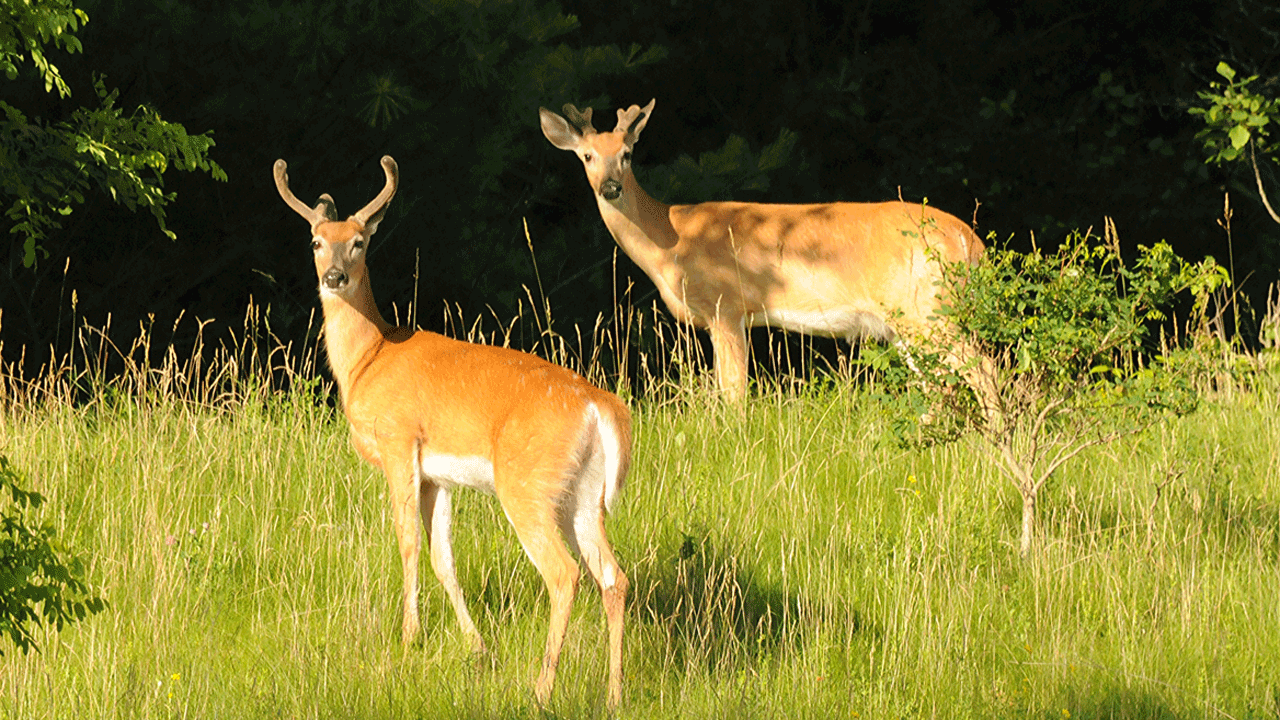

Well … Maybe we’re giving Wisconsin’s Capitol dwellers too much credit. While the rest of North America spent this spring and early summer acknowledging the growing threat of chronic wasting disease, the Badger state’s Legislature voted twice more in June to wish CWD away.

Recent votes in the Wisconsin Senate and Assembly suggest its lawmakers aren’t up to tackling the Badger state’s tough choices on chronic wasting disease.

In their latest oath of loyalty to the Flat Earth Society, Wisconsin’s Senate and Assembly Republicans voted 20-13 on June 14 and 60-37 on June 21, respectively, to enact a sunset provision on the state’s deer baiting and feeding ban.

Currently, when CWD is found in a county, deer baiting and feeding are banned indefinitely in that county and adjoining counties within 10 miles of the disease. The Legislature’s proposed sunset would end those bans after three years in the diseased county and two years in adjoining counties if no other deer tests positive for CWD.

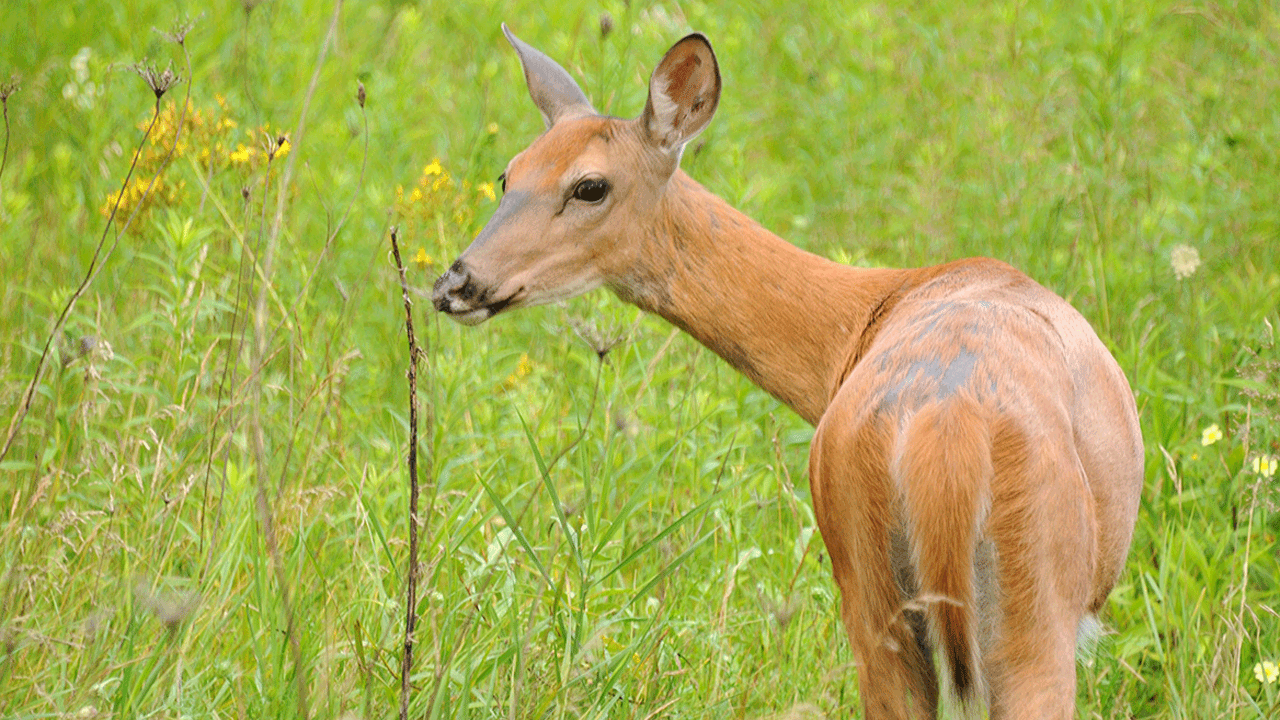

Trouble is, through previous budget cuts targeting the state’s Department of Natural Resources, lawmakers made it impossible to systematically test for CWD, even when it’s found in new areas. Granted, no one knows for certain how CWD spreads, but no one disputes that it’s inherently unhealthy to put animals in nose-to-nose contact at bait/feed sites routinely freshened and fermented with their own saliva, urine and feces.

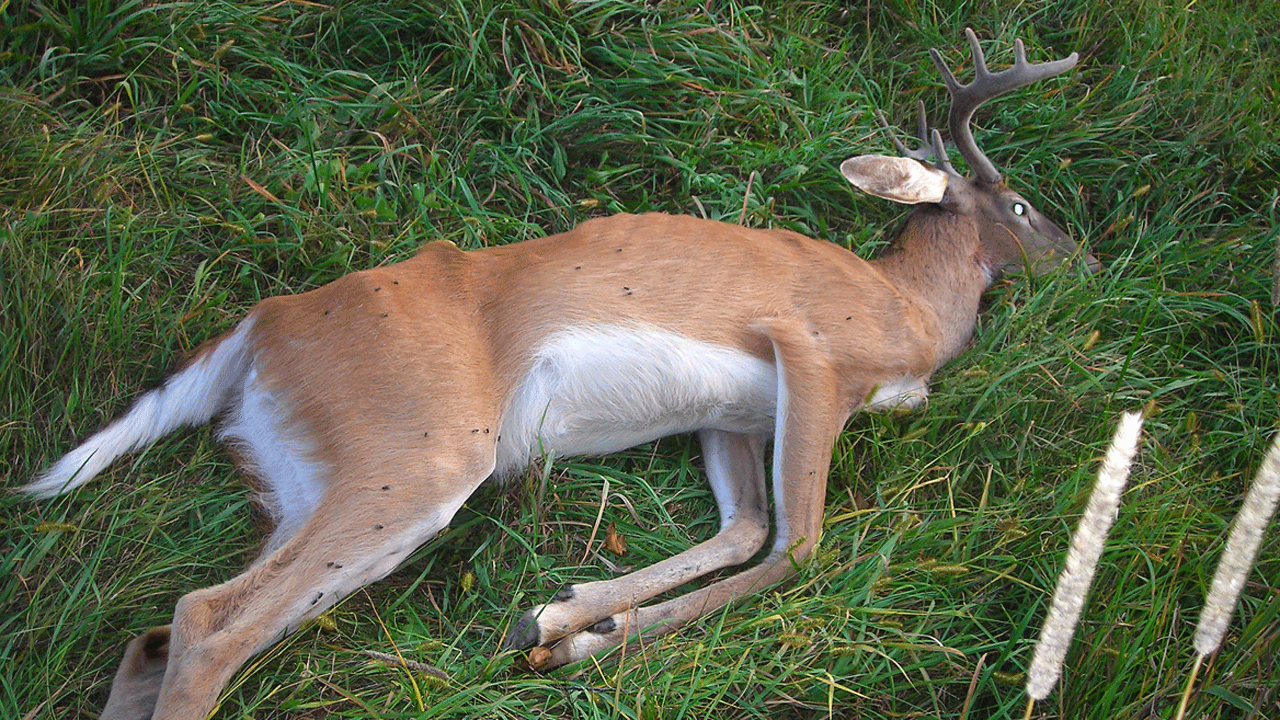

This 2.5-year-old buck succumbed to CWD in southwestern Wisconsin.

And yet our lawmakers vote to let their constituents bait and feed deer rather than ensure scientific documentation of CWD on the landscape.

Therefore, the Wisconsin Conservation Congress, whose top officers have openly supported Gov. Scott Walker since his 2010 election, sent a letter June 29 urging his veto. The 360-member WCC serves as lay advisers to the seven-citizen Natural Resources Board, which sets DNR policy. The WCC consists of five elected delegates from each county.

“I’m hearing from a lot of people on those bills, and it’s all negative,” said WCC Chairman Larry Bonde of Kiel. “People are very upset. I’ve called the governor’s office to register the Congress’s opposition, and I’m urging our members to call, too. It’s time they tell lawmakers there will be a lot of moderate Republicans looking to Democrats for help if this continues.”

Bonde said the WCC is reminding the governor that its leaders followed his suggestion this spring by requesting all 72 County Deer Advisory Councils devote a specific meeting to review CWD policies, including the state’s baiting/feeding law. The result? Most counties supported a statewide baiting/feeding ban, and opposed the sunset clause.

And that was no fluke. Sportsmen voting at the WCC/DNR statewide spring hearings in 2006, 2008, 2011, 2014 and 2015 supported statewide baiting/feeding bans by landslide percentages. The county votes those years were, respectively: 74-23-3, 60-35-5, 82-17-1, 92-7-1 and 87.5-12.5.

“The governor made this an initiative, so I hope he reads the information we gathered for him,” Bonde said. “If he wants to run for re-election, he needs to know how we feel. I’ve been in the Conservation Congress a long time, and I’m starting to appreciate the fact that a split government is the one that best serves the people.”

States now dealing with CWD wish they had invested more time and effort into widespread testing to check for the always-fatal disease.

Meanwhile, rational people beyond Wisconsin’s borders are issuing new warnings while trying to advance science’s understanding of CWD.

For example:

— A Canadian study starting in 2009 found five of 18 macaque monkeys exposed to CWD contracted the always-fatal disease. Three got sick by eating CWD-infected materials, two from meat and one from brain matter. The other two got sick after their brains were injected with CWD-infected materials. Results aren’t yet in on the study’s other 13 macaques, a species that is genetically closer to humans than squirrel monkeys, which previously were found susceptible to prions.

— Therefore, Health Canada recently updated its CWD risk advisories, noting that although extensive disease surveillance in Canada and elsewhere has not found direct evidence that CWD has infected humans, its potential for transmission to humans can’t be ruled out. Health Canada said Canadians should consider that CWD has the potential to infect humans.

— Researchers Mark Zabel and Aimee Ortega of Colorado State University want to set controlled fires on National Park Service lands in Arkansas and Colorado to see if killing plants laden with CWD-causing prions lower the odds of healthy deer getting sick. Although the fires aren’t hot enough to destroy prions, they might hinder disease spread by reducing the availability of CWD-contaminated browse foods.

— Norway plans to try wiping out a specific herd of 2,000 reindeer after finding CWD in three animals earlier this year.

— At the third “summit” meeting convened June 7-8 in Austin, Texas, by the National Deer Alliance, the nearly 120 attendees from conservation organizations and wildlife agencies agreed CWD poses the greatest risk to North America’s deer herds and deer hunting.

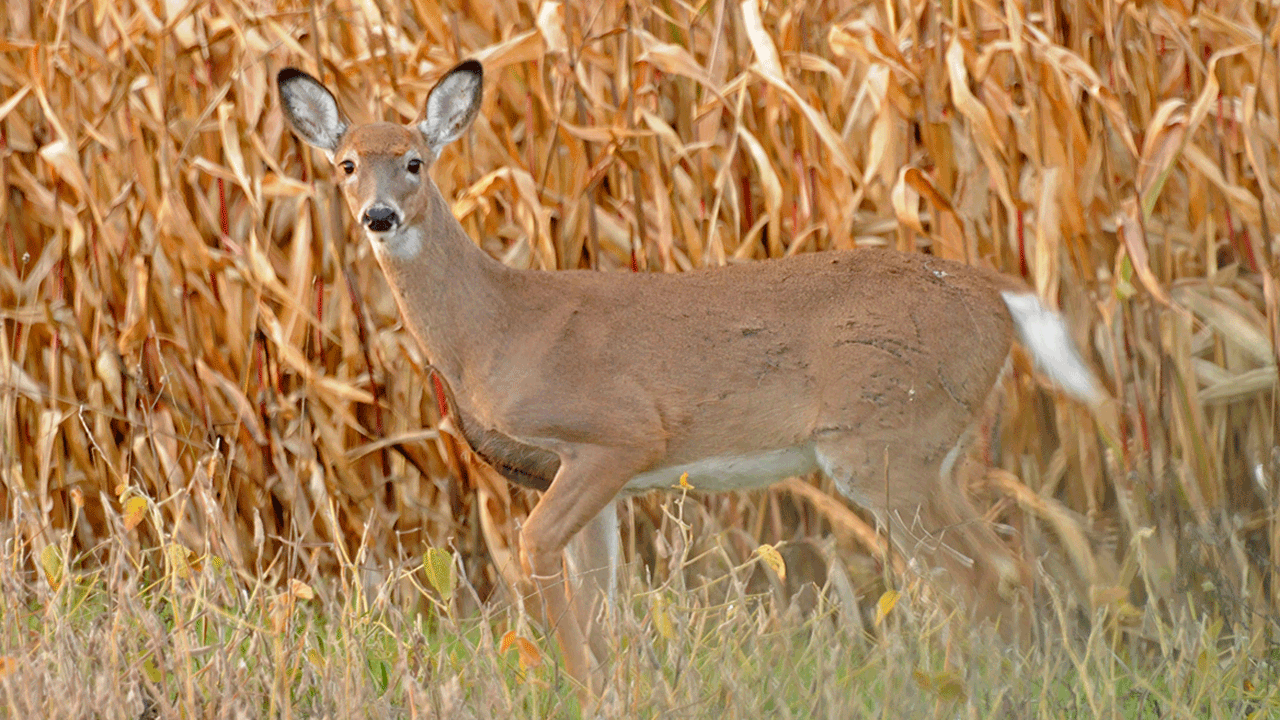

The deer herd in one 10-by-20-mile area in northwestern Arkansas had a 23 percent CWD infection rate in 2016.

When a panel of five state-agency wildlife biologists was asked if they wished their states had done anything differently, given CWD’s presence in 24 states, they agreed they should have put more effort into sampling and surveillance.

Ralph Meeker of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, said it felt like a “punch in the gut” when the agency found CWD was not only present in January 2016, but it had obviously been there awhile. Arkansas has since confirmed CWD in 207 whitetails and six elk. Further, a random harvest last fall of 266 whitetails from a test area roughly 20 miles long and 10 miles wide in northwestern Arkansas’ Newton County found 62 deer (23 percent) had CWD.

Given such evidence, as well as spiking CWD rates in parts of Wisconsin that once had only one CWD case, one must wonder how Wisconsin’s lawmakers keep ignoring this disease.