image courtesy JWT for thetruthaboutguns.com

Sweet baby Jesus this gun is pretty.

Taylor’s & Company has imported a limited run of nickel-plated Smith & Wesson Model 3 Schofield break-top revolvers. The Schofield is one of the iconic guns of the west, with a rich history. It would be hard to do such a storied horseman’s sidearm justice, but in every way, this Italian-made Uberti replica does just that. It is an exceptional revolver.

The Schofield is derivation of the famous Smith & Wesson Model 3. Originally made in 1870, the top-break Model 3 has the distinction of being the first cartridge revolver to become standard issue in the US Army.

Although the United States Army would end up ordering thousands of the guns over time, as would several other countries, it was the Czar of Russia that really got the ball rolling. Starting in 1870, Czar Alexander the II ordered over 40,000 of No. 3 revolvers in different variations.

Unfortunately for Smith & Wesson, the Russians loved the design enough that they copied it and refused to pay for most of the orders already made to the czar’s specifications. The result was catastrophic, almost bankrupting Smith & Wesson.

To make matters worse, unlike the czar, the United States infantry was underwhelmed by the Model 3 during its early trials. They preferred the simple design of the Colt Open Top and then the Single Action Army, Model P “Peacemaker.”

Everyone admitted that the S&W was twice as fast to reload as the Colt, and it seemed to be more accurate as well. But infantry commanders argued that the soldiers didn’t use their sidearms much, rarely had need to fire more than six shots, and the Colt’s accuracy was good enough to get the job done.

They preferred the Colt partially because it was deemed to be more durable than the Model 3, especially during a pistol whipping. I kid you not. Apparently the Smith & Wesson’s two-piece frame had a tendency to come apart when used as a bludgeon, whereas the Colt remained together…a big win for the Colt. As a former Joe myself, I hate to admit it, but the big army was probably right. Give a Joe something he can break and he will.

It was during its early trials and use by the US Army that then Major George Schofield took an interest in the sidearm. He chose to look at the problem not by walking in an infantryman’s boots, but from the perch of his 10th Calvary saddle. Schofield recognized the value in the Model 3’s break-top, fast ejection design for a cavalryman riding on horseback. He just had a few changes to make.

He wrote to Smith & Wesson with his ideas, including moving the barrel latch to the frame, as well as a single-toothed spring and a cam released that snapped the extractor/ejector back down when that tooth made contact with the lower strop. He also suggested making the rear sight integral to the latch.

He was granted patents for these modifications on June 20th, 1871 and April 22, 1873, as all S&W Model 3 “Schofields” after that would be marked until the end of their production.

Schofield’s design was a big improvement over the previous Model 3s. In 1875 The military ordered 3,000 of the new Schofields in what would be a relatively short-lived contract and put them in the hands of the 4th, 9th, and 10th cavalry.

Just two years later Smith & Wesson would further refine the Model 3, incorporating Schofield’s designs in their “New Model No. 3” and their variations, the “Frontier” and “Target” models. Although they never became as popular as the Peacemaker, the original and New Model 3 Schofield patented revolvers became a well-known and much desired sidearm of the late 19th century.

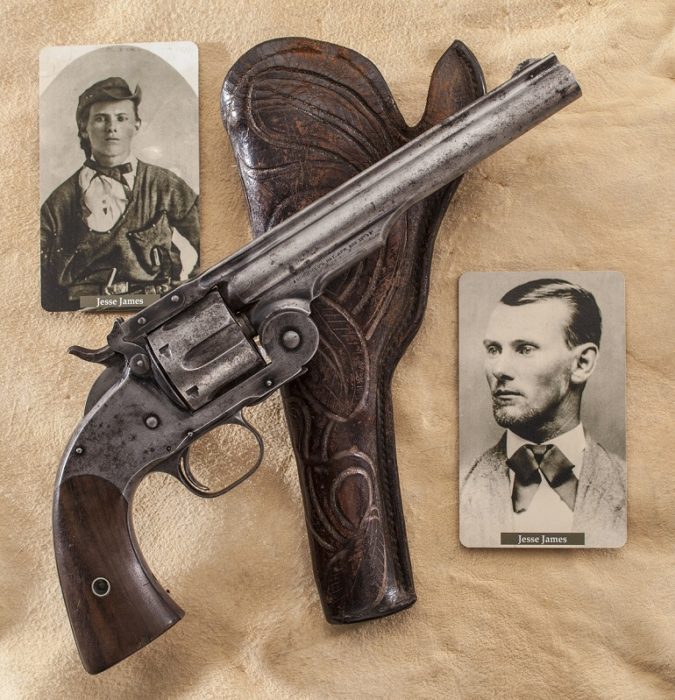

The Schofield versions were favored by many famous professional gunslingers on both sides of the law. Jesse James was known to carry two pistols on him, one a Colt and one a Schofield. When Bob Ford shot James in the back, he did so with a Schofield. Sherriff Pat Garret, the man who killed Billy the Kid was known to carry and use the Schofield patented pistol, as was Texas outlaw John Wesley Hardin and even President Theodore Roosevelt.

The Model 3 was used throughout the American West, as well as in several American wars, all the way up into the 20th century. Its clockwork action, accuracy, and speed became icons of the era. It was one of the foundational models of the Smith & Wesson enterprise, even though it was never much of financial success.

I could write more than I have time for about Lt. Colonel George Schofield himself, as well as the fortuitous arrangement he had with his brother, who headed up the Army Ordnance Board.

By all accounts, George Schofield was a frenetic inventor, and likely suffered from significant manic depression. Sadly, he ended his life with one of his own revolvers. His obituary, dated December 17, 1882 in the New York Herald stated that “he had been crazed for eight or ten days over some invention of his, and it is supposed that in a moment of temporary insanity he shot himself.”

courtesy findagrave.com

Taylor’s & Company sells several versions of the S&W Model 3, including a few Schofields. This one is a definite up-class version, not just working well, but looking incredibly good too.

The entire revolver is nickel finished and mirror polished. Be careful when shooting this gun in bright sunlight, as its reflection may blind pilots in low-flying aircraft. The finish is perfect throughout the gun, down to the tiniest parts. Beyond the even and smoothly polished nickel, take a look at the screws.

All of the screws on the frame are colored a beautiful blue. They contrast and set off the mirrored nickel well, and add even more class to a gun with a lot of attention to detail. By the way, most of the these photos were taken after the first 100 shots, and the gun was only wiped down with my T-shirt. You should have seen it out of the box!

Nickel plating can be pretty and durable, or pretty and easily chipped. I can safely say this one is very much on the durable side.

I shot the heck of the gun, shooting the first 100 rounds — all my own hand loads — in about three hours time and it got dirty. I tried it out in a few different holsters, doing my best to figure out how to quickly draw a seven-inch barrel gun. (It turns out, I can’t.) I also played with the latch, releasing it and flipping it back up probably a couple hundred more times.

There are two “cocked” positions for the Schofield. The first slightly cocked position is how it was designed to be carried. This both removed the integral firing pin attached to the hammer from the top of the primer and also allows the shooter to pull back on the release latch integral to the rear sight.

Upon release, the muzzle swings down, and the extractor comes up, pushing all of the cases up. A little more force and the barrel tips back at the shooter, the cylinder comes forward, and all of the cases fly out in front of the shooter.

Some claim that the revolver can then be reloaded again entirely with just one hand although I certainly can’t figure out how, especially on horseback. Once new cartridges are inserted, a quick flick of the wrist sends the muzzle up and the cylinder back down, locking it back in place. The gun is ready to fire again.

That whole sequence is fascinating to watch, and I did it over and over, even with empty cases, just to watch them fly out of the chamber again. It’s just fun.

The upside to you, dear reader, is the knowledge that even after the shooting and drawing and just tons of goofing around, there’s still no obvious wear on the gun.

Ah, but is it authentic? Did shooters in the latter part of the 19th century really like a nickel finish on their guns? Yes, they absolutely did, and they could get them straight from the factory. In fact, starting as early as 1860, any revolver could be ordered from Smith & Wesson with either a blued finish or nickel-plated.

Almost all of the early No. 3s marked “Schofield’s patents…” went to the US Army for use by the cavalry. As these guns hit the surplus market, they began to be picked up by everyday civilians, law enforcement, and companies alike.

They became very popular with the US marshals, as well as Wells Fargo. Believe it or not, before they were a bank repeatedly fined for unethical conduct and defrauding account holders, Wells Fargo was pretty well-respected. Their investigators were, in particular, seen as the professional gunslingers of the day. They were the “operators” of 1890. As a company, they chose the Schofield as their sidearm of choice, buying hundreds of the revolvers and shortening the barrel of many of them down to five inches for ease of concealment and carry.

Not long after, much of the public did the same thing, having their barrels modified from the cavalry’s original seven inches down to five. Some took the extra step of nickel plating them as well, just like some of the “operators” did. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

This revolver from Taylor’s & Company is chambered in .38 Special, a cartridge that wasn’t available in the Model 3s from the factory. The first S&W revolvers to be chambered in 38-40 Winchester (similar to the modern-day .40S&W) came out in 1876, but Smith & Wesson didn’t start chambering pistols in .38SPL until 1898.

It’s possible that some of the Schofields in private hands were chambered on custom order in .38-40 Winchester, but I can find no actual examples of that chambering. However, the .38SPL is only one of the chamberings offered by Taylor’s & Company. They also offer models in .44-40 and .45 Colt. The original caliber used by the cavalry was the now practically extinct .45S&W, a black powder cartridge closely duplicating a light-loaded .45ACP.

Although not entirely authentic, the .38SPL is a phenomenal shooter in this gun. There is very little recoil. I had several people fire this revolver, including a new shooter at The Range at Austin, a 9-year-old girl who had never shot a gun in her life. She had no issues at all, other than it was a little heavy for her.

Even with hot .38SPL+P commercial ammunition, muzzle rise is minimal, including shooting single-handed. I would not expect most commercial .45LC to be any different, and only the .44-40 would likely show a real difference in recoil. Even so, with the .44-40 or hot .45LC loads suitable for close range hunting, recoil would be very manageable, even by the inexperienced shooter.

As I had already put more than 100 rounds through the Schofield during a series of drills, I wasn’t surprised that it was a gun capable of considerable precision. I just didn’t realize how precise that really was.

After my second shot at 25 yards using Remington’s 130gr FMJ UMC round on a paper, target I was genuinely confused. I had the gun resting on bags on my shooting bench. My hands were on bags, my arms were on bags, and my chest was leaning in and against the bench. I was still. I had taken my time during the shots, and my sights were on target the entire time.

How, then, did I miss the paper entirely?

My third shot confirmed what many of you are likely suspecting. A hole in a hole is awful hard to see at 25 yards. Just for visual effect, I moved to shooting steel.

I shot 60 total rounds for accuracy with this pistol. I used commercial rounds from Remington UMC, Winchester 158gr LRN, and Armscor 158gr FMJ rounds. Shooting four rounds of five shots from each manufacturer, not a single one averaged larger than one inch at 25 yards. That lighter weight Remington round scored 3/4″.

I shouldn’t have been particularly surprised, as this is the second Uberti pistol I’ve reviewed, and I’ve bought two others. They’ve all displayed this level of accuracy. Like the others, part of this accuracy comes from good sights, a long sight radius, and a great trigger.

The rear sight is integral to the cylinder release latch. At the top of the simple V notch are deep horizontal grooves and a deep oval cut for your thumb. Way up there behind the muzzle is a simple, thin metal blade front sight.

Between the two, there is plenty of space to see the target, but by aligning the base of the V rear with the front sight, a great deal of precision is possible. For most of my groups, there was relatively little horizontal spread where the rounds would lay.

Unfortunately, at 25 yards, they lay about three inches to the left of the target. I had several shooters try the gun, and the results were the same for all of them. The gun shoots nice, tight, consistent groups. They’re just consistently to the left. And the sights aren’t drift adjustable,

I would have guessed the trigger pull weight was about 2.5lbs with no creep and a clean break. It’s actually heavier than that, measuring at 3lbs 10oz. It feels much lighter and there’s no way I would change a thing about it.

I shot a total of 200 rounds through this revolver for testing. One hundred of those were commercial rounds and 100 were my own hand-loads shooting one a 170gr SWC pushed by 4.2gr of Unique powder. Other than the Unique making the nickel finish filthy, I never had any issues with reliability in any way.

At no time did the gun fail to fire or cycle. With a flick of the wrist, the break-open revolver never failed to eject all cases cleanly. I lubed the gun prior to shooting with EEZOX and performed no other maintenance for the first 100 rounds. Those first 100 were all lead cast rounds, so I fully cleaned the bore after that, prior to shooting the commercial loads and testing for accuracy.

That’s not my usual procedure, but it didn’t seem fair to lead the bore up really good and then test for accuracy with commercial ammunition. As it is, I have zero reservation as to the reliability of this revolver.

The grips on this short run release are a synthetic resin made to look like mother of pearl. Many folks scoff at such fancy looking grips, thinking they aren’t authentic. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Long before the Gucci GLOCK, shooters from all walks of life were fancying up their guns, I can find quite a few photos of old revolvers with mother of pearl grips, including ones used in the saddle by working lawmen. This Schofield patented revolver below is particularly embellished, as befitted its owner, Annie Oakley.

Cavalrymen would have been issued walnut grips on their service revolvers, and these authentic grips are available from Taylor’s & Company as well. The imitation mother of pearls grips on this fancier model are well done and perfectly usable.

I shot this gun in the Texas Hill Country “Spring” heat, ranging from 90 to 102 degrees. Unsurprisingly, my hands were a little sweaty during a few of the courses of fire, and the smooth grips didn’t help. But they didn’t hurt much either, as the tiny amount of recoil exhibited from the three-pound revolver just didn’t move the gun enough to matter.

Despite the heat, I couldn’t help but try my hand at some quick draw and rapid fire single-action shooting. The key word in that last sentence is “try”.

I spent a good amount of time drawing from my Simply Rugged holster and shooting two shots into a 10-inch circle at 15 yards. My better times were around 1.8 seconds. In cowboy action shooting, that time would be good enough to keep me from getting laughed off the range, mostly due to the kind nature of the folks that attend those events.

In my defense, the hammer of the Schofield is a little farther forward than the Peacemaker’s, and the hammer throw is also a little longer, so the Model P is always going to be a little faster. That’s one of the many reasons it’s so popular to this day.

Also, the seven-inch barrel of the Schofield is a whole lot of steel to clear and point before it gets up there in the first place. But mostly, I’m just slow and I always have been. My time to draw and fire six shots into the same 10-inch circle at 15 yards averaged 4.56 seconds. If that sounds bad, well it’s not nearly as discouraging as it is fun.

It was hard to give this one back, and I have little doubt I’ll end up picking one up at some point. Likely with the walnut grips and chambered in .45 Colt. The gun is just too accurate, too easy to shoot, and too much fun not to own one.

It’s a great look back into history at one of the competitors of the Colt, and one of the foundations of the Smith & Wesson legend as well. Taylor’s & Company picked a good one.

Specifications – Smith & Wesson Model 3 Schofield

Barrel Length: 3.5″,5″,7″

Caliber: .38SP, .44-40, .45LC

Capacity: 6

Weight: 3.5″=2.85 lbs, 5″=2.90 lbs, 7″=2.97 lbs

Finish: Nickel Finish with charcoal-blue screws

Grip/Stock:2-piece Walnut or Pearl

Manufacturer: Uberti

Sights: Blade Front, Rear sight on back of barrel

Overall Length: 3.5″=9.25″, 5″=10.75″, 7″=12.75″

MSRP: $1,522.00

Ratings (out of five stars):

Style and Appearance * * * * *

Fine as hell, y’all.

Historical Accuracy * * * *

There is a transfer bar for safety, which is a good idea. There also appears to be a slight thickening of the top strap over the original’s, I assume in order to accommodate the larger .45 Colt. Also the grips aren’t real mother of pearl, but imitation. Real mother of pearl grips would add at least $100 to the price of the gun. Beyond that, it appears to be completely accurate, down to every marking and detail. As fancy as this gun looks, many originals were just the same.

Reliability * * * * *

The Smith & Wesson Schofield loaded, unloaded, and fired perfectly every single time, no matter what I put through it.

Accuracy * * * * *

All one-inch groups and many less at 25 yards with cheap commercial ammunition. An exceptional shooter.

Overall * * * *

I really enjoyed this gun, but the sights being slightly off kept it out of my 5-star category. Beyond that, it’s a beautiful, functional, surprisingly accurate revolver. Plus, it’s just fun to shoot.

In writing this article I relied heavily on three sources. The Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Smith & Wesson Handguns and one of my absolute favorites, Age of the Gunfighter.