The temperatures hit 60 in late March, which melted the last remnants of winter’s snow.

That’s nice, but it also exposes winter’s flotsam: cans, bottles, paper cups, cigarette butts and other junk that people flick into snow when no one’s looking. And there it sits, mostly hidden, until the snow melts and homeowners and other litter-picker-uppers scour their property lines in spring.

That’s what took us down our driveway one recent Saturday afternoon. A line of white cedars bordering the asphalt marks the property line between our place and the neighbor’s. Once these trees grew the past 20-plus years and filled the gaps between their trunks, their lower branches spend their winters trapping garbage like gill-nets snaring smelt.

Our garbage-pickup duties reminded me that the trees weren’t always there. Back when Gordy Latraille rented the house next door, we often visited along this stretch. Our driveways met there until his landlord quit sharing the driveway’s upkeep costs with me. He told Gordy that he’d have to be content with the property’s main driveway, and quit sharing mine.

Gordy understood. He didn’t expect me to let him use a driveway that I owned and maintained alone. He even helped me plant the trees and lay some railroad ties to block the rental property’s driveway from mine.

Memories of a successful hunt long ago also brought back some regrets and sadness.

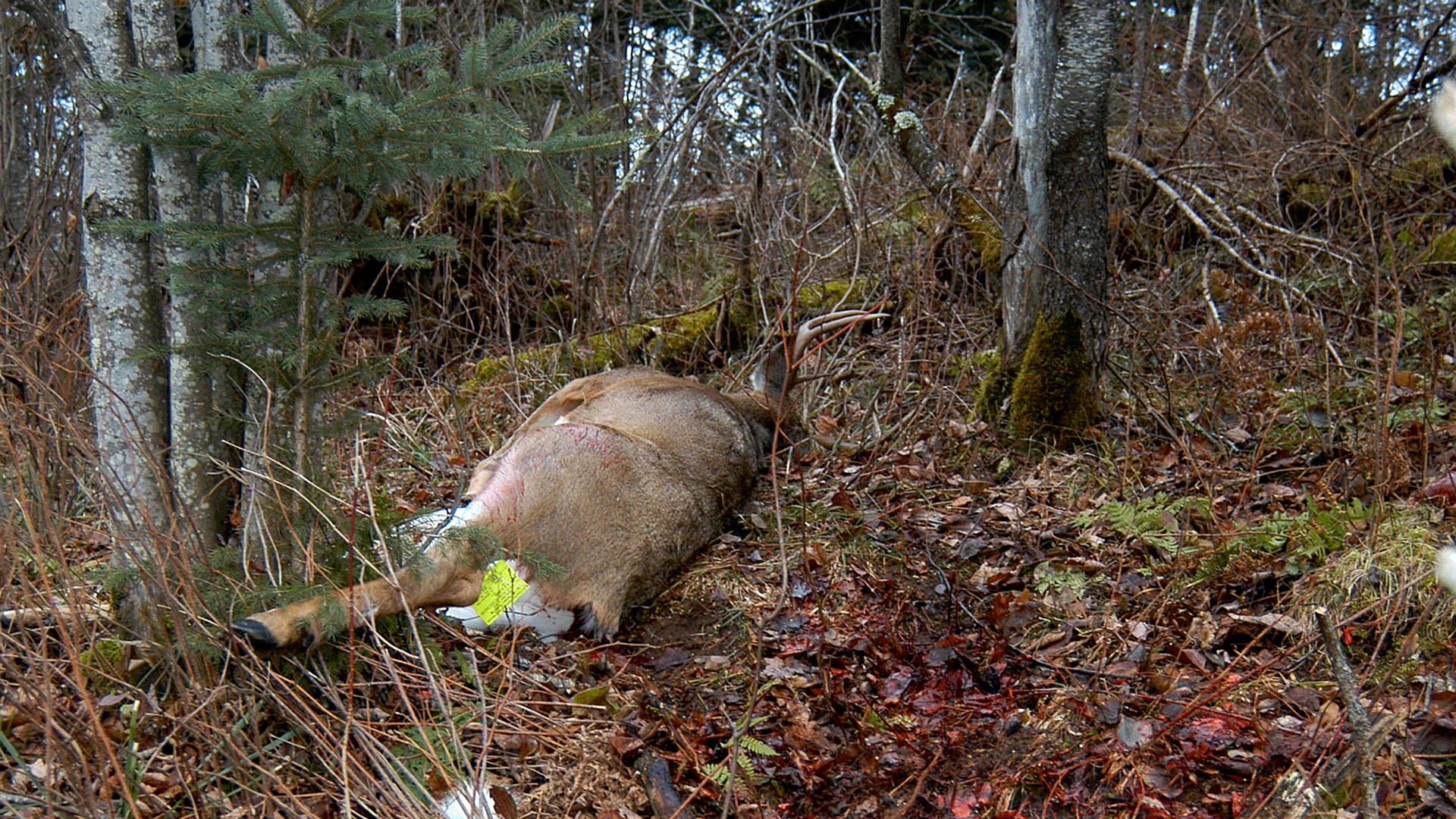

But Gordy’s long gone now, and so I paused while picking up winter’s trash last week. Something made me recall a successful deer hunt in November 1998 in Manitoba. Night had fallen dark and clammy by the time I had my buck field dressed and loaded into the pickup truck.

As I shut the tailgate and shone my flashlight around the truck to ensure I retrieved all my gear, I glanced at the buck’s entrails in the weeds. That sight, too, had unexpectedly invoked a memory of Gordy’s friendship and past considerations.

For several years, I had always made one last cut or two at my deer’s gut piles to retrieve their hearts and livers for my next-door neighbor. Gordy savored those delicacies, and often swapped me huge bags of potatoes he had gathered while visiting his hometown in North Dakota.

At times I would also give him a deer or a half-deer because I knew he valued the meat as much as I did. Not only that, but it was the neighborly thing to do, and he deserved it. I could trust him to watch my home, and maybe even check in and help out Penny and my daughters when I was away on business.

Those considerations ceased being relevant when Gordy died unexpectedly in autumn 1998 before I could even get my bows and guns ready for the fall’s hunting seasons. He was only 48.

As snow disappears each spring, it can reveal things that laid hidden for months.

Gordy was one of those gracious guys who, despite having a nice wife and three loving sons, had a rough freakin’ life. I never got all the details because I thought it impolite to pry, but I knew his Vietnam experience left him unable to work because of long-term health and stress problems. His visits to the VA hospital in Tomah, Wisconsin, had become more frequent than he cared to discuss.

On top of that, he was forever driving back home to North Dakota to attend the funerals of close relatives, many who also died before their time. God help me, but when he drove off on such trips, I often wondered when his turn would come.

My worst experience as a neighbor came a couple of warm summers before when my daughters yelled downstairs for me to go to the door. They said Gordy needed to talk to me. I grumpily greeted him because I was preoccupied with deadlines and tardy manuscripts.

Gordy stammered something about a lot of people arriving shortly, and asked if it would be OK if they parked in my driveway. Then he blurted out, “My wife died last night, and the family’s coming over from North Dakota.”

I stared in shock as Gordy blinked back tears and explained that his 42-year-old wife, mother of his three teen-age boys, had checked into the hospital the previous night because she wasn’t feeling well. She was dead before dawn.

Man, what did this guy do to deserve such deep, chronic pain?

Even though we never hunted or fished together, those were the two standard topics for our driveway visits. When Gordy learned venison is seldom in short supply in my home, but that I wasn’t a fan of the heart and liver, he hesitantly asked if I would save the organs for him. His appreciation was so sincere during the subsequent gift-givings that I somehow felt guilty for all the deer hearts and livers I had previously left for foxes and opossums.

Fallen deer often provided great meals for a next-door neighbor.

Before long, I was offering the deer itself when my freezers reached capacity. Gordy would send over a son to help me skin a deer. We would then carry the pink carcass into Gordy’s kitchen and lay it atop the table. Later, he would call me over to proudly show his meat-processing operation, and drop friendly hints about never tiring of fresh venison.

All those memories flashed through me the other day as I dropped trash into the plastic bag. Those thoughts also took me back to that night in a wooded marsh in Manitoba, and the gut pile still containing a buck’s heart and liver.

After I drove off that night, I’m sure coyotes or raccoons appeared under the full moon, and ate what would have been a meal Gordy savored. I can’t help but think the scavengers had the Vietnam War to thank for those protein-rich organs I left behind.